James Tiptree, Jr. (also known as Alice Sheldon and Raccoona Sheldon) is primarily known for gender-bending, boundary-pushing work in short-form SFF—but Tiptree was also a poet, as well as a novelist with two published novels. My Patreon backers voted to pick Tiptree’s first novel, Up the Walls of the World, for me to read and review this week!

But first, a note: Readers voted on this book and I wrote this review before the current controversy related to the end of Tiptree’s life, which involved a murder-suicide and/or suicide pact. The Tiptree Award is currently in the process of being renamed (a decision I support—and I also don’t think awards should be named after specific people or novels in general, either). I feel that the review contributes to the overall discussion of Tiptree’s contributions to the genre, focused on a topic that is perhaps more easily approachable: critiques of Tiptree’s own published work; so I haven’t changed the column besides adding this note and changing the name of the award at the end.

Tiptree’s short stories have been very influential for me both as a reader and as a writer—I discussed this in the Letters to Tiptree anthology edited by Alexandra Pierce and Alisa Krasnostein. But this was my first encounter with Tiptree’s novels, which are often considered lesser works when compared with the better-known stories. Up the Walls of the World is described as follows in Tiptree’s biography, James Tiptree, Jr.: The Double Life of Alice B. Sheldon by Julie Phillips: “the noisy, sexy, funny, painful real life of Tiptree’s best stories, the rude noise in the face of injustice, is missing from the novel.” This is a bold claim; does it bear out?

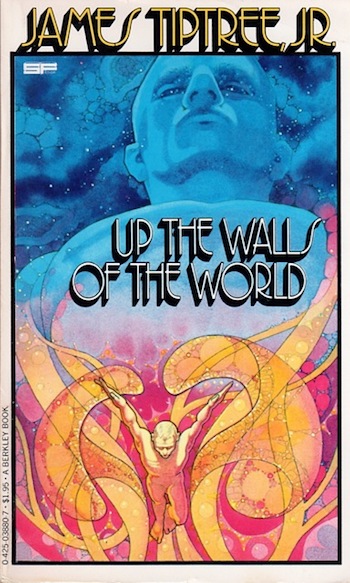

I felt that Up the Walls of the World had moments that were unlike the short stories, but it was also considerably more complex and subtle—especially about gender. Tiptree is usually portrayed as a woman writing stories about masculinity under the cover of a male pseudonym, but in reality neither Tiptree’s gender identity nor sexuality are as straightforward as that description suggests. Tiptree experienced gender dysphoria and struggled greatly with related emotions—something that is also apparent in Up the Walls of the World, first published in 1978 by Berkley Books.

The novel has three main plot threads that start separately, then intertwine throughout the book. First, a giant, mysterious alien creature is flying through space, fulfilling a mission that has to do with the destruction of planets. Second, we get to meet the telepathic inhabitants of the planet Tyree, beings reminiscent both of squids and bats who live on the eternally blowing winds of their home, never descending to the surface. Third, we find ourselves on Earth in the quasi-present-day of the novel, where Doctor Dann works on a secret government project to investigate the capabilities of telepathic people—and tries to handle the multi-drug addiction he’s developed while coping with the death of his wife.

It is probably not much of a spoiler to reveal that the telepathic humans and the telepathic aliens end up in touch, amid the looming threat of planetary destruction. But what happens after that is more difficult to anticipate. The plot embarks on many twists and turns, with the internal mindscapes, the grittily ordinary setting of military installations, and the world of the strange alien planet all complementing each other as it unfolds.

The novel is also filled to the brim with gender- and sexuality-related topics, in non-straightforward ways that in many respects make it fascinating even today…and in some others, have aged the text quite painfully. Before I started the book, I’d read in multiple places—including in the immense queer SFF bibliography Uranian Worlds, by Eric Garber and Lyn Paleo—that the novel featured only minor lesbian themes; in other reviews, these were even described as the blink-and-you-miss-it type. My reading experience and conclusions couldn’t have been more different.

Up the Walls of the World does feature a queer couple, the young human telepaths Valerie and Fredericka. Fredericka also goes by Frodo and is a Lord of the Rings fan. Their relationship is very openly described as romantic—it is the plain meaning of the text. There is a reason why I am not sure it can be classed as lesbian per se, though; namely that Fredericka/Frodo is explicitly referred to as an “androgyne” (p. 297), prefers to use a male name, and otherwise seems like the archetype of the young, introverted, and nerdy nonbinary person who was assigned female at birth—back in a time when “nonbinary” as a word was not in common use yet, but the intent is clear.

The aliens from Tyree, the Tyrenni, also have difficulties with their birth assignments in ways that are sometimes recognizably trans to the present-day reader. While they have often been described as an inversion of human male/female gender roles, their genders are more complicated than that, to begin with. Their sexual dimorphism is much more pronounced than that of humans. Men are very large-bodied and they bear and raise children. They also have a larger telepathic field, which they use to “Father” children. Women are hunters and explorers, smaller and more adventurous—but they also still possess lesser social power, just like human women.

The main Tyrenni point of view character, Tivonel, establishes her cisness in her very first chapter: “Do I want to be an abnormal female like the Paradomin, wanting to be a Father myself? Absolutely not; winds take the status! I love my female life—travel, work, exploration, trade, the spice of danger. I am Tivonel!” (p. 7). But we find out later about the Paradomin in great detail. They make attempts to transition, both socially and physiologically. They change their names to male forms, and part of that is explicitly status-related, similar to historical women crossdressing for social advancement. But part of it is related to their desire to Father children, which leads them to transition, in modern terms. They perform special exercises involving caring for small, semi-sentient pets in place of children, in order to increase their telepathic fields—thereby bucking the preexisting social-political attitudes that Fathers’ larger field is inherent in their biology. (We do not get to see the alien trans women, if they exist.)

There is also a large amount of gendershifting sprinkled throughout—not just in small details (e.g., when a random alien of a different species is labeled “hermaphroditic”), but also in a more pervasive, structural way. As the telepathic characters come into contact with each other, they not only find themselves in each other’s minds, but also in their bodies—leading to many situations of men in women’s bodies, and also vice versa. Tiptree deals with this much more sensitively and insightfully than many present-day authors of body-swapping science fiction. People clearly maintain their gender identity despite their temporarily jaunts into differently-sexed bodies, but the experience also leaves its mark upon them. (It is clear upon reading that a lot of thought went into describing telepathy in this work.) Even some of the unambiguously cis men have ambiguous gender experiences. Without giving away any plot points, I can say that Doctor Dann has a paranormal ability that is usually gendered female, and his use of it is described as “dizzying, transcendent, transsexual” (p. 273); though from the context, this can also mean that it goes beyond sexuality, but that’s certainly not the only possible reading.

The Paradomin are portrayed as conflicted and conflictual, and here we can see echoes of second-wave feminism, which was highly divided about transness. The Paradomin quasi-feminists are not very positively depicted as a group; they are suffering and they don’t know whether they want to transition for status or out of a deeper-seated need, or both. This very much echoes Tiptree’s life experience passing as a mysterious man only communicating in letters, and then getting outed as Alice Sheldon in 1977—which impacted the reception of this novel itself upon release, shortly after this information came to light. Tiptree felt that the novel was received less positively because of it, and there is evidence of that according to Phillips; though sometimes editors simply bemoaned the present tense used throughout the book, instead. (This is done so transparently and with such skill that I only realized afterward, upon examining the novel’s reception and reviews.) The book is an achievement and reads as such. But I cannot unambiguously endorse it, either, because as Tiptree attempted to come to terms with gender within the novel’s context, the text’s portrayal of race suffered as a result.

From here, major spoilers follow, which is why I’ve left this topic to the very end—but I cannot let the issue go undiscussed even if it reveals plot twists, because it is one of the key aspects of Up the Walls of the World.

Margaret Omali is a major character and the love interest of Doctor Dann. She also has massive genital dysphoria. But she’s not trans…the only framework for an expression of dysphoria that occurred to Tiptree is female genital mutilation. And while I cannot fault the author for trying to engage with such heavy themes, even in the absence of a framework like present-day transness, here the book becomes very painfully dated.

Margaret Omali is Black and is the daughter of a Kenyan immigrant. On a trip to Africa as a 13-year-old, she experiences genital mutilation as part of a traditional rite. This is portrayed crudely, becomes the explanation and focus for her entire personality, and also turns upside down all the aspects of Margaret’s character that could have been considered subversive. For instance, we find out early that she prefers modern furniture. I was cheered by this—not least because this represents a direct trope subversion of the exotic African Black woman, even if done in a not particularly sensitive way, since it’s shown through the eyes of a rather racist white man: “None of the cryptic African art [Dann] had expected” (p. 23). (Also, to allow myself a moment of chirpiness, I like modern furniture! And identifying with characters…) But then it all takes a sinister turn: Margaret likes modern environments because her genitals were mutilated: “She can only bear distance, be like a machine. Even color is dangerous; those neutral clothes, that snow-bound apartment. And no reminders of Africa, never.” (p. 128)

Margaret is a mathematician and computer scientist. She is an older version of Frodo in many ways, and both characters do read as if they have more than a little of the author in them. But the narrative doesn’t allow her to engage in those abstract interests for their own sake—only as a result of her trauma. (Frodo likewise cannot be allowed happiness: Frodo and Valerie break up near the end, and the other characters repeatedly remark on Frodo’s sadness.)

Certainly, there are many women even today who experience genital mutilation. This does not reflect their experience; this is an outsider portrayal that falls into many of the possible traps of such narratives. We also only see it reflected through other characters’ thoughts, effecting a double dehumanization that is further reinforced by the use of the “inhuman” computer metaphor. The doctor even gets a chance at playing white savior, in the literal sense. Tiptree has written many insightful stories about imperialism, but here the gender aspects serve to obscure those structural details. And while the novel is immensely complex and multifaceted—I feel there are many other details I could not even begin to tackle in the scope of a book review, and I am also currently working on a longer analysis—the anti-Blackness drags it down even as the plot turns into an oddly welcoming sort of found-family narrative.

The ending is more successful again, as it enlists telepathic mind contact in the aid of gender expression: “IT IS A PROTO-PRONOUN, AN IT BECOMING SHE BECOMING THEY, A WE BECOMING I WHICH IS BECOMING MYSTERY.” (P. 313, all caps in the original.) Characters join to form a plurality so that they no longer need to have a gendered pronoun. This was so new a concept at the time of the book’s release that I could not find anyone even remarking on it, and it is poignant to this day.

I feel that Up the Walls of the World has been overlooked, and at best has been interpreted as containing only minor themes touching on sexuality. After reading it, I strongly feel that it is instead a work that provides key insights into how Tiptree thought about gender—including gender dysphoria, gender roles and stereotypes, and more. The ending doesn’t touch on the grimdark themes that many readers and reviewers expected from the author, but this choice becomes clear as we consider that the conclusion explicitly tackles gender pronouns in a positive way. To me, the handling of race, Blackness, and African identity are the aspects that have dated the novel the most—after reading, I could not decide whether to immediately rush to reading Tiptree’s other novel or immediately rush in the opposite direction—but this facet of the story wasn’t a major focus of the book’s relatively negative critical reception upon release, as far as I could tell in retrospect. It feels like the gender emphasis was so ahead of its time that it was unintelligible to many readers, and the bulk of it simply did not fit into the “gay or lesbian” rubrics available both at the time and for decades henceforth. I kept on nodding while reading, but all the terms I would use to describe the plot details mostly became widespread in the 2000s onward. The gendered aspects of the novel remain highly relevant today.

An endnote: I am on the jury of this year’s now-in-the-process-of being-renamed Tiptree Award, focusing on speculative work that explores or expands the concept of gender. If you read something from 2018 or 2019 that you’d like us to consider, anyone can nominate work of any length for this award! Send us your recommendations.

While Tiptree’s Brightness Falls from the Air lies in wait on our living room table (ready to pounce?), next time I will discuss the first English-language novel which mentions neopronouns, The Kin of Ata are Waiting for You by Dorothy Bryant… a work which also suffers from some of the very same issues as Up the Walls of the World.

Bogi Takács is a Hungarian Jewish agender trans person (e/em/eir/emself or singular they pronouns) currently living in the US with eir family and a congregation of books. Bogi writes, reviews and edits speculative fiction, and is a winner of the Lambda Literary Award and a finalist for the Hugo and Locus awards. You can find em at Bogi Reads the World, and on Twitter and Patreon as @bogiperson.